-

Who we are

WHO WE AREThe International Organization for Migration (IOM) is part of the United Nations System as the leading inter-governmental organization promoting since 1951 humane and orderly migration for the benefit of all, with 175 member states and a presence in 171 countries.

-

Our Work

Our WorkAs the leading inter-governmental organization promoting since 1951 humane and orderly migration, IOM plays a key role to support the achievement of the 2030 Agenda through different areas of intervention that connect both humanitarian assistance and sustainable development.

What We Do

What We Do

Partnerships

Partnerships

Highlights

Highlights

- Where we work

-

Take Action

Take Action

Work with us

Work with us

Get involved

Get involved

- Data and Research

- 2030 Agenda

Lack of Data on Children and Women Migrant Deaths Highlighted in New UN Migration Agency Report

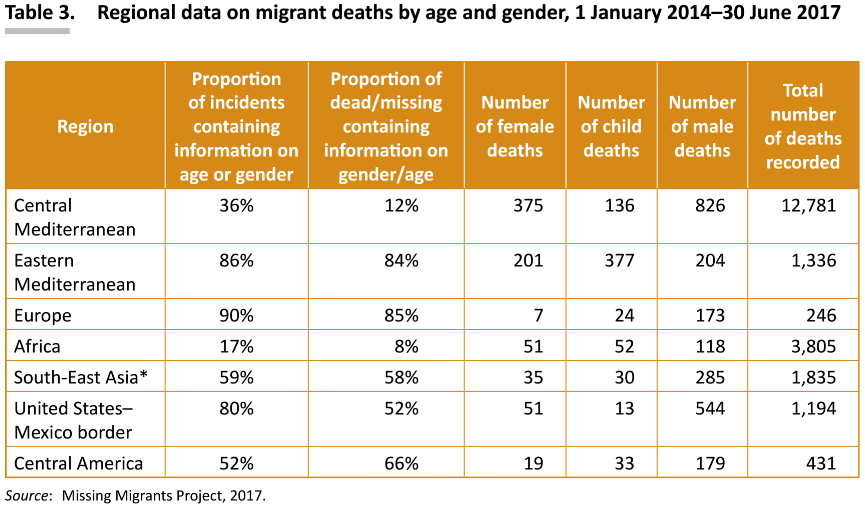

Berlin – Between January 2014 and June 2017 IOM´s Missing Migrants Project recorded 665 migrant children deaths, a figure which is likely to be three times as high based on the number of children migrating, both accompanied and unaccompanied, worldwide. The lack of information and data disaggregation by gender and age is highlighted in the recently launched report Fatal Journeys Volume 3 – Part 1: Improving Data on Missing Migrants, prepared by IOM´s Global Migration Data Analysis Centre.

In the Mediterranean, the deaths of 658 women and 532 children have been confirmed out of nearly 13,000 total fatalities recorded in three and a half years. However, the age and gender of more than 10,000 migrant deaths in the Mediterranean is unknown.

As stressed in the report, collecting and analysing data on migrant deaths and disappearances is hampered by several challenges. Information on age and gender of the deceased specifically is highly contingent on the identification of bodies. As a consequence, in incidents in which many migrants are lost in shipwrecks, the gender and age breakdown of the decedents remains unknown. This is of concern given that the majority of migrant deaths globally are recorded as taking place over water.

Additionally, despite women representing just under half of the world’s migrant population (117 million in 2015), many data sources implicitly or explicitly assume that migrant populations are dominated by adult males.

Media articles on migrant deaths often fail to mention the gender and age of the decedents, as do nearly all aggregate figures from NGO and official sources. This means that female and child migrants who die during their journeys may not be identified as such, especially in situations complicated by trafficking.

Differing policies and practises used to track and record arrivals of migrants from country to country make developing strategies to estimate more accurate numbers of female and children among the dead more difficult.

For instance, while the number of unaccompanied or separated child arrivals is publicly available information in Greece and Italy, in Spain it is not. Children may also avoid being registered by authorities, or claim to be older than 18 so that they can continue their journeys and not be taken into protection.

As a result of these difficulties, the completeness of migrant deaths data varies greatly by region. Of the incidents of death recorded by the Missing Migrants Project, only half of incidents have information on either age or gender, but the proportion in each region around the world ranges from 5 to 85 per cent.

Consequently, the 4,207 migrant decedents who were identified as men, women or children represent less than 20 per cent of the more than 22,500 migrant deaths recorded between January 2014 and June 2017.

Expanding data collection and reporting could enable empirical analysis of trends in migrant fatalities, which could further strengthen policies and programmes to reduce risks on migrant routes. Where possible, this data should be sex- and age-disaggregated, to lead to identification of the dead, and to better understand the risks specific to women and children on migration routes worldwide.

Fatal Journeys Volume 3 was funded by the UK’s Department for International Development and can be found here:

https://publications.iom.int/books/fatal-journeys-volume-3-part-1-improving-data-missing-migrants.

For more information, please contact:

Julia Black, Missing Migrants Project in Berlin, Tel: +49 30 278 778 27, Email: jblack@iom.int

Frank Laczko, IOM Global Migration Data Analysis Centre in Berlin, Tel: + 49 30 278 778 20, Email: flaczko@iom.int