Enrique Delgado with wife Haidy and daughter Paola.

Enrique Delgado with wife Haidy and daughter Paola.Breathing Life Anew

For Enrique Delgado — a migrant from Venezuela residing in Panama — diagnosed with multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB), the psychological effects and the sense of isolation that result from the disease are more traumatic than the expenses associated with it, or even the threat to life. "I have to live in isolation in my own house, wearing a mask..." He lived in constant fear that he would pass on the illness to his wife and daughter and many times contemplated committing suicide.

Enjoying a New Life and Career in Panama

Following his migration to Panama, Enrique's career took an upward turn and life was looking very promising. He was promoted to Regional Coordinator of Service at Sony's Headquarters for Central American Operations. In this role, Enrique needed to travel two to three times a month to the Caribbean, Central American and Eastern American countries that made up their territory.

These frequent business trips demanded a lot from his body as the time difference would require his internal clock to adjust, the compressed timetable and high expectations would build up the stress level in his system, the hectic itineraries would have him up on his laptop way into the night — and require him to get up early. Now read on

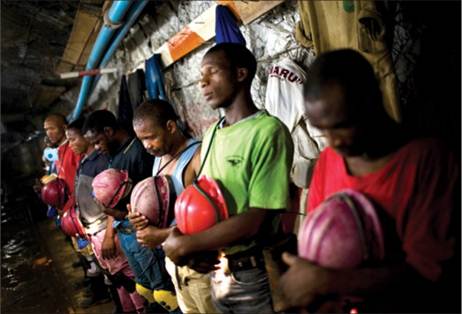

South Africa's Migrant Mining Labor Force: Bringing Home the Bacon and TB

South Africa's mining industry is highly dependent on migrant workers coming from neighboring countries like Lesotho, Swaziland and Mozambique. These men travel from their villages to their mineral-rich neighbor to earn a living and to take home some income to their families. Unfortunately, they often bring home something else. Tuberculosis.

South Africa's mining industry is highly dependent on migrant workers coming from neighboring countries like Lesotho, Swaziland and Mozambique. These men travel from their villages to their mineral-rich neighbor to earn a living and to take home some income to their families. Unfortunately, they often bring home something else. Tuberculosis.

Highest Rate of Infection

South Africa's mine workers have the highest infection rate of TB in the world. Mining activities are pregnant infection sites for tuberculosis and at least a third of infections in the southern region of Africa can be traced to the industry. Each year, new people are infected. Research findings show that 3% to 7% of miners develop TB infections every year.

Partnerships: Stopping TB as One

Multisectoral partnerships are critical for migration health. Working together with the varied (and sometimes apparently contradictory) interests of stakeholders in TB and migration can generate a strong momentum towards achieving TB prevention goals.

The Working Group on TB and Migration of the International Union Against TB and Lung Disease is a good example.

As the global TB community has been working towards evaluating Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 2015 TB targets and developing a post-2015 strategy, the Group has provided a platform where National TB Programs (NTPs), immigration health authorities and health professionals – including those involved in migrant TB screening, human rights experts, migrant representatives, UN agencies, and donors like the Global Fund – can come together.

At the Union's 2013 annual conference in Paris, the Group presented symposia on such topics as environmental migration, disease burden among global migrant groups, and the role of employers in supporting TB care for migrant workers.

Watch out for more updates in the TB and Migration section of IOM's website (http://health.iom.int/) and the UNION website (http://www.theunion.org/).

Ma Khine Khine Win receives TB advice from an outreach health worker

How to Reach the Missing Three Million

Ma Khine Khine Win could easily have become one of the missing three million. Born and raised in a small village in Tharyarwati township, Bago District, Myanmar, she moved with her family to join other migrants seeking work in a village in Kyaikmayaw township, Mon state – over 300 km away. She knew she was suffering from poor health, but poverty prevented her from accessing health care.

Ma Khine Khine Win could easily have become one of the missing three million. Born and raised in a small village in Tharyarwati township, Bago District, Myanmar, she moved with her family to join other migrants seeking work in a village in Kyaikmayaw township, Mon state – over 300 km away. She knew she was suffering from poor health, but poverty prevented her from accessing health care.

"I had had a cough off and on since before leaving my home village, which never really went away. After arriving at [her new village] Taungkalay, I gradually began to lose weight, felt constantly fatigued from the hard work and had a prolonged fever. My cough became worse, even though I didn't have a sore throat, and I noticed blood tinges in my sputum. But, without a penny, how could I get a consultation from a private clinic?" Now read on

Sustained Action for Migrants' Health in a Post-2015 TB Strategy

As medical doctors, we are trained to identify disease agents, attack them with effective drug therapies and interrupt the natural history of infections that could lead to severe disability or even death for our patients.

As public health practitioners – we decide when more is needed. Disease control is not merely about one patient – it is about detection, treatment and care in the population or communities at large.

But as migration health experts, we face even more daunting challenges. How do we deal with, prevent, treat and control diseases and health conditions among people on the move – in sending, transit and receiving countries – satisfying immigration and health legislation, and ensuring equitable use of often scarce resources? And how do we address stigmatization and possible human rights violations?

In no public health topic are these questions more important than in the ongoing discourse on a post-2015 TB strategy. At its very core, TB is a disease of immense public health significance even within national boundaries, with some 22 countries classified as "High Burden" (i.e., out of every 100,000 people, 100 or more would have active TB disease). The rest are classified as mid-to-low burden.

TB is a social disease. If you think that it is simply caused by a micro-organism (Mycobacterium Tuberculosis), think again. TB infection is driven by social factors, focusing on the poor, marginalized and socially vulnerable.